The purpose of countermeasures to protect the public

"Countermeasures" are the things we do to reduce the dose to the members of the public affected by an accidental release

of radioactivity. The prompt countermeasures are: shelter, evacuation and stable iodine.

Principles

The NRPB introduced the principles that countermeasures should be justified (do more good than harm)

and optimised (the quantitative criteria used to introduce and withdraw countermeasures should be such

that public protection is optimised) (Docs NRPB Vol 1 No 4.). The paper then goes on the present Emergency

Reference Levels (ERLs) that provide a cost-benefit type optimisation function for the usual early countermeasures.

Countermeasures and how they work.

Shelter.

Shelter simply consists of asking everybody to go indoors, shut doors and windows and turn off

any air-conditioning units. This is shelter in place as opposed to shelter in a facility outside of the affected area.

It provides protection in two ways

(1) it provides shielding from radioactivity

in the air and on the ground outside the building and

(2) the air concentration of radioactivity is less inside

the building than outside so inhalation dose is reduced.

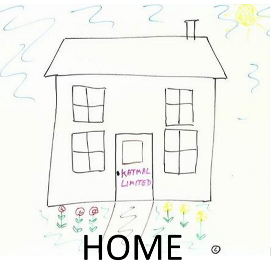

The figure shows the airborne concentration of a gas inside and outside a house for a short

release and for a longer release. It shows that the airborne concetration into the house remains lower than

that outside the house while the release is happening. This is one reason why people are better off in buildings

than outside while the release is underway. Importantly the figure shows that after the release it is important

to open doors and windows to reduce the inside concentrations.

The NRPB advice is that "shelter in a reasonably built reasonably airtight house reduces external doserates

by a factor of 10 and inhalation by a factor of 3. (Docs NRPB Vol 1 No 4.)

The NRPB advice is that "shelter in a reasonably built reasonably airtight house reduces external doserates

by a factor of 10 and inhalation by a factor of 3. (Docs NRPB Vol 1 No 4.)

Shelter is consistent with the national generic advice "go in, stay in, tune in" given in the

Preparing for Emergencies. What you need to know booklet.

.

There are important questions about how long you can ask an unprepared community to shelter for. Difficulties can arise, for example,

at the time that the school day ends as families will want to be reunited. Other difficulties involve vulnerable groups who

are getting support in their homes. Sooner or later supplies and or patience will run out.

An interesting pamphlet on an American Authority’s (Macomb County, Michigan) view on how to prepare for shelter in place can be found here.

Evacuation.

Evacuation involves completely removing people from the area and saves ("averts") all of the dose

that would have been received after the person leaves the affected area. You do need to be careful to avoid

increasing people's dose by unwisely breaking shelter for an inefficient evacuation.

Evacuation can be very difficult for some vulnerable groups.

Cabinet office

advice is that 'An evacuation should only be carried out if the benefit of leaving an area significantly

outweighs the risk of sheltering in place' warning that 'The over-riding priority must be the safety of the public. Evacuation should not be

assumed to be the best option for all risks, and it may not be the safest. Buildings offer

significant protection against most risks, and immediate shelter may be safer for the public,

at least initially. Evacuation can be traumatic, especially for vulnerable people, and it can

be disruptive to business and the local economy.'

Stable Iodine.

Nuclear reactors accidents can release radioactive forms of iodine which can damage the

thyroid gland, particularly of young people. Taking a sufficient dose of stable, that is non-radioactive,

iodine stops the body absorbing radioactive iodine by exceeding the body's ability to hold more i.e. by

saturating the body in stable iodine. This is very effective provided the stable iodine is taken quickly

enough - its basically a race to the thyroid between the radioactive and non-radioactive iodine.

The diagram shows that if the taking of the iodine tablet is delayed then its effectiveness is reduced.

Because of this the operators of nuclear reactors in the UK "pre-distribute" stable iodine tablets to homes

and businesses in a preagreed area around the site and make arrangements to inform people in this area that

they should take them.

It is important to note that stable iodine is only useful for accidents at operating reactors since radioiodine has a short half life

and its concentration drops rapidly when the reactor is shutdown.

For accidents in the UK, and indeed most of the world, it would be expected that controls on the use of contaminated food would prevent any

significant uptake of radioiodine through eating. The main uptake would be as a result of breathing the radioactive plume as it passed by. Thus

the countermeasure must be applied during the release phase to be effective.

1999 advice from the World Health Organisation (here)

suggests that this countermeasure is ineffective, even damaging, for people over 40.

Countermeasure Decisions

The use of shelter, evacuation and stable iodine can reduce the radiation dose to the public but all have a cost associated.

This cost is not just the cost to the nuclear utility and Local Authority of maintaining and testing plans but also the cost

to the people involved in terms of disruption to their private and professional lives and the risks inherent in the

countermeasure. An extreme example of this is the number of hospital patients that are reported to have died in the evacuation

of the 20km zone around Fukushima

(Lancet Report) but more usual

costs are the inconvenience of being required to evacuate or being confined to within buildings both of

which can disrupt family life and work.

As discussed in the section on avertable dose Public Health England

(formerly NRPB) have considered the costs of benefits of the three early countermeasures and produced a table of Emergency

Reference Levels

(NRPB Reference)

above which the countermeasures are of nett benefit.

A problem with setting countermeasures by comparing avertable dose with ERLs is that avertable dose cannot, by its very nature,

be measured. This is because:

(1) avertable dose is a prediction of the future whereas measurements are in the past;

(2) The public dose rate is difficult to measure as it is dominated by inhalation dose the estimation of which requires

knowledge of the isotopic composition and chemical and physical form of the airborne activity. These are not easy to

predict or measure.

To determine the need for countermeasures by comparison with the ERLs requires an understanding of the inhalation

doserate for the affected people from the time the countermeasure is effective to the end of the release.

That is, we need to understand how long it will take to

implement the countermeasure and how the accident will develop (how long will the leak continue? Will the release rate increase

or decrease in that time? Will the isotopic composition change? Will the weather conditions change?

What will the effected members of the public do in the time that they

may be exposed).

This is why Public Health England, when they were the NRPB, advised using Action Levels to decide if countermeasures

should be applied. These Action Levels are based on a series of assumptions about the isotopic composition and duration

of a future release and provide a rule of thumb for countermeasure advice in the early stages of a response.

If you want to know more about countermeasure strategy and how to determine one for a site contact infoweb1@katmal.co.uk.

Back to top | Return to Content Index | Next page